“I don’t want to be the president of the world,” Donald Trump declared in Washington on 4 April. “I’m the president of the United States. And from now on, it’s going to be America first.”

A week later, he stood alongside the secretary-general of Nato and told reporters at the White House: “Right now, the world is a mess. But I think by the time we finish, I think it’s going to be a lot better place to live ... because right now it’s nasty.”

It has been a brazen reversal in both word and deed. In the past 10 days, Trump has launched 59 Tomahawk missiles at a Syrian government airbase, dropped the biggest non-nuclear bomb ever used in combat on eastern Afghanistan and deployed a naval strike group to waters near North Korea.

For good measure, having lambasted China and lauded Russia during the election campaign, Trump now lauds China and lambasts Russia while saying of Nato: “I said it was obsolete. It’s no longer obsolete.”

The screeching U-turn has thrilled establishment Republicans and foreign policy hawks while mortifying the isolationist backers of “America first”, a phrase denounced by the Anti-Defamation League for its links to 1940s Nazi sympathisers, who helped him snatch the election while branding Hillary Clinton a warmonger.

Senator Lindsey Graham, one of his defeated opponents, tweeted: “I hope America’s adversaries are watching & now understand there’s a new sheriff in town.” Charles Krauthammer, a conservative columnist known to be on Trump’s radar, wrote in the Washington Post: “The traditionalists are in the saddle. US policy has been normalised. The world is on notice: eight years of sleepwalking is over. America is back.”

And the political website Axios noted: “In less than a week, Trump has morphed into a guy who could almost be mistaken for a conventional Republican president. Trump appeared in the White House’s East Room yesterday and gave remarks that could’ve come from the mouth of George H W Bush.”

But it remains uncertain whether the president, whose past statements have been known to contain three different policies in a single paragraph, is merely acting on instinct or now shaping a clear foreign policy doctrine – and indeed whether such a doctrine is either possible or desirable.

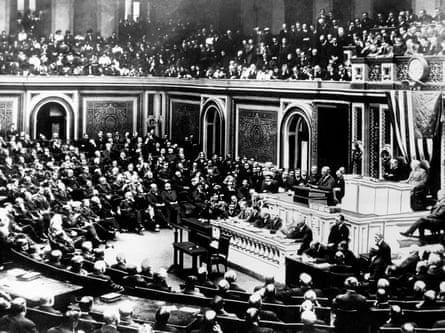

No student of history, Trump may or may not have been aware that his attack on Syria coincided with the 100th anniversary of America’s entry into the first world war. That had been spurred by a speech in which Woodrow Wilson threw down the gauntlet to Congress: “The world must be made safe for democracy.”

These have since been described as the eight most important words in US foreign policy history: a mission statement for the world’s policeman. From the second world war to Vietnam through two Iraq wars, it has provided the philosophical underpinning for interventionism.

But George W Bush’s ill-fated invasion of Iraq in 2003 in search of non-existent weapons of mass destruction cast a long shadow over Barack Obama, arguably influencing his decision not to strike Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad’s regime but rather make a deal with Russia to remove his chemical weapon stockpile.

The attack on a town in Syria’s northern Idlib province that killed dozens of people implies that Obama’s 2013 policy was less successful than billed. Secretary of state John Kerry had declared: “With respect to Syria, we struck a deal where we got 100% of the chemical weapons out.” But Antony Blinken, a former deputy secretary of state, admitted in the New York Times last week: “We always knew we had not gotten everything, that the Syrians had not been fully forthcoming in their declaration.”

At the time, Trump urged Obama against military intervention in Syria. But Trump was for the Iraq war before he was against it. During the election campaign he offered a creed of isolationism while promising, almost in the same breath, to “bomb the hell out of Isis”, increase military spending, as well as speaking admiringly of General George Patton, Dwight Eisenhower and Harry Truman for having the “guts” to drop a nuclear bomb. He has a history of foreign policy flip-flops, and in this he is hardly alone.

His shifts of the past two weeks have multiple causes. A president long addicted to cable news has said several times how he was moved by the primetime images of poisoned children and “beautiful babies” in Syria. His daughter Ivanka, herself a mother, was among those who weighed in on the horror of what Assad had done.

Shifting fortunes in the West Wing are a factor too. Ivanka and her husband, Jared Kushner, are said to be increasingly influential on Trump as they worry about his negative headlines. His national security adviser, HR McMaster, is also exerting his authority, removing chief strategist Steve Bannon from the national security council. Bannon, former head of Breitbart News and principal flag waver for the hardline “anti-globalists”, finds himself increasingly marginalised, with Trump describing him in the Wall Street Journal as “a guy who works for me”.

Then there is the simple reality check that faces any new president. In the wake of Trump’s election victory, Obama told reporters: “Regardless of what experience or assumptions he brought to the office, this office has a way of waking you up. And those aspects of his positions or predispositions that don’t match up with reality he will find shaken up pretty quick, because reality has a way of asserting itself.”

There was a vivid example of this when Trump expressed his hopes to Chinese president Xi Jinping that Beijing’s pressure could steer North Korea away from its nuclear efforts. “After listening for 10 minutes, I realised it’s not so easy,” he told the Journal. “I felt pretty strongly that they had a tremendous power” over North Korea, “but it’s not what you would think.”

There has also been a willingness to heed advice that torture does not work. But as his scattergun tweets demonstrate, Trump is profoundly capricious and unpredictable, driven by a desire to “win” above all. A man who has ranged across the political spectrum from Democrat to far-right conservative may change his mind or reverse gear again, especially under pressure from a nationalist base accusing him of betrayal.

Rightwinger Ann Coulter, author of In Trump We Trust, wrote this week: “Was America strengthened by the Iraq war? The apparently never-ending Afghanistan war? Vietnam? This is how great powers die, which is exactly what the left wants.”

She added: “We want the ‘president of America’ back – not ‘the president of the world’.

Tossed by events, doctrines are hard to define in meaningful detail. Whereas Wilson called for the world to be “made safe” for democracy, Obama’s mantra was reportedly: “Don’t do stupid shit.” To date, Trump’s appears to be: “I do change and I am flexible, and I’m proud of that flexibility.”